Devin Nunes Made an Ass of Himself Again

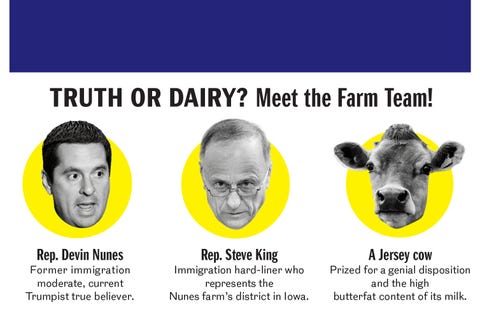

Devin Nunes has a secret. Nunes is the California Republican and chairman of the Firm Intelligence Committee who has become famous in the Trump era for using his position as a battering ram to discredit the Russia investigation and protect Donald Trump at all costs, even if it ways shredding his own reputation and the independence of the historically nonpartisan commission in the process.

First elected to Congress in 2002, Nunes wasn't always like this. At one time he was known for his contained streak. When a new form of radical House Republicans pushed its leadership to shut downwardly the government in 2013, Nunes attacked them equally "lemmings with suicide vests." In 2015, during another tumultuous flow of House GOP infighting, I interviewed a broad cantankerous department of the chamber'south Republican leadership, and Nunes stood out for comments he made near how his colleagues and constituents were siloed in right-wing echo chambers and increasingly reliant on this or that "conspiracy theory" rather than "something that is mostly true." In hindsight, he was prescient near the direction of his party: A few years after, a bona fide conspiracy theorist, one who credited Alex Jones with his victory, was elected president.

Instead of standing the fight, Nunes served on the president'southward transition team and became Trump's most important defender in Congress. He has used the Intelligence Commission to spin a baroque theory well-nigh alleged surveillance of the Trump campaign that began with a fabricated-up Trump tweet near how "Obama had my 'wires tapped' in Trump Belfry." Indeed, Nunes has worked closely with the White House to investigate the FBI rather than the FSB (the KGB's successor), virtually famously by attempting to undermine the Russia investigation by releasing a partisan report—the so-chosen "Nunes memo"—that cerise-picked evidence to charge the FBI of bias in its effort to obtain a warrant to monitor the communications of Carter Folio, a Trump foreign-policy advisor.

For more bombshell political stories, breaking news, and daily commentary sign up for the Esquire Newsletter.

SUBSCRIBE

Nunes has always been reliably conservative, but on some issues, he has cleaved with his political party. He has long supported moderate immigration reform, for instance, including amnesty for many undocumented people living and working in the U. S. But as Trump has instituted a draconian policy of goose egg tolerance for all undocumented people and argued that every undocumented individual should be deported, Nunes has been silent. More recently, every bit Trump and the House Republicans accept historic Immigration and Community Enforcement and the agency's ambitious tactics, Nunes has followed accommodate. On CaRepublican.com—a Nunes-created news site, which mimics the Drudge Study—he now regularly highlights manufactures attacking Democrats for being insufficiently supportive of ICE'south raids and deportations.

Which brings u.s.a. back to Nunes's secret.

Nunes grew up in a family of dairy farmers in Tulare, California, and as long equally he has been in politics, his family dairy has been central to his identity and a feature of every major political profile written almost him. A March story in National Review is emblematic. It describes how Nunes'due south family unit emigrated from the Azores in Portugal to California's Cardinal Valley, "a fertile, sunny Eden," and how the family unit "worked and saved plenty coin to buy a 640-acre farm outside Tulare." The soil of the Key Valley is depicted as almost sacred in these articles. National Review quotes a 1912 Portuguese immigrant farmer who wrote that when he grabs a clump of dirt, "I feel equally if I had just shaken easily with all my ancestors." As recently as July 27, the lead of a Wall Street Periodical editorial-page piece about Nunes, which featured a Tulare dateline, emphasized the dairy: "It's 105 degrees every bit I stand with Rep. Devin Nunes on his family unit's dairy subcontract." Last year, Nunes noted in an interview with the Daily Beast—headline: "The Dairy Farmer Overseeing U. Due south. Spies and the Russian federation Hack Investigation"—"I'm pretty uncomplicated. I like agriculture." The Daily Beast noted, "The cows are not far from his mind. He keeps in regular contact with his blood brother and father nigh their dairy farm."

So here'southward the underground: The Nunes family unit dairy of political lore—the ane where his brother and parents work—isn't in California. It's in Iowa. Devin; his blood brother, Anthony Three; and his parents, Anthony Jr. and Toni Dian, sold their California farmland in 2006. Anthony Jr. and Toni Dian, who has also been the treasurer of every one of Devin's campaigns since 2001, used their greenbacks from the sale to buy a dairy eighteen hundred miles away in Sibley, a pocket-sized town in northwest Iowa where they—too as Anthony 3, Devin'southward but sibling, and his wife, Lori—have lived since 2007. Devin's uncle Gerald still owns a dairy dorsum in Tulare, which is presumably where The Wall Street Journal's reporter talked to Devin, and Devin is an investor in a Napa Valley winery, Alpha Omega, only his firsthand family'due south farm—as well as his family unit—is long gone.

There'southward nothing particularly strange nigh a congressman'southward family moving. Only what is strange is that the family has apparently tried to conceal the move from the public—for more than a decade. Equally far as I could tell, until late August, neither Nunes nor the local California press that covers him had ever publicly mentioned that his family dairy is no longer in Tulare.

For case, in 2010 Nunes traveled to northwest Iowa to entrada for Steve King, the nigh anti-immigrant member of Congress, who now represents Nunes's parents, brother, and sis-in-law in Sibley. It was an unusual place to find Devin Nunes, given that at the fourth dimension he wasn't known to be hostile to immigrants in the way that has made Male monarch, who has chosen illegal immigration a "slow-motion terrorist attack," so infamous.

Rex's office posted a printing release online announcing that the town-hall effect would exist in Le Mars, a boondocks 50 miles southwest of Sibley, and included some biographical information well-nigh Nunes, including this fact: "Congressman Nunes' family unit has operated a dairy farm in Tulare County, California for three generations." There was no mention that the Nunes family actually lived up the road in Sibley, where they operated a dairy. Foreign.

In June 2009, an obscure dairy trade publication, Dairy Star, ran a profile of the Nunes family dairy in Sibley. The article documents how the Nunes family, "recent transplants to the Midwest," emigrated from Portugal to California to Iowa and started NuStar Farms, which Anthony Jr. manages with his son and wife.

The commodity mentions numerous Nunes family members, including Uncle Gerald, who was yet back in California, and infant Maci, "the first Nunes to be born exterior of California or Portugal," just there is one person missing from the commodity: Devin Nunes.

Why would the Nuneses, Steve King, and an obscure dairy publication all conspire to hide the fact that the congressman's family unit sold its farm and moved to Iowa? I went to Sibley to find out. Things got a little foreign.

The first thing I did when I landed in Iowa, on Baronial 27, was call Jerry Nelson, the writer of the Dairy Star commodity. I'd read through Nelson'southward other online manufactures. He'southward funny and smart and could hands be a columnist at a major newspaper. When he was xxx, he almost died in a bizarre manure-pit blow, and he told me that since then he's lived every twenty-four hours like information technology'southward a blessing.

He was upfront and clear about why Representative Nunes wasn't included in the Dairy Star profile of the Nunes family unit and the movement to Iowa: The family asked him not to mention Devin. "They said, 'Our blood brother's involved in politics and we're non going to talk about information technology and that's that,' " Nelson told me. "And I said, 'Okay, we're here to talk nearly dairy farms.' "

Sibley, Iowa, is in the far due north of the state, xx minutes from the Minnesota edge. It has twenty-six hundred people and feels smaller. The biggest attractions in town are a well-groomed golf grade and a high-terminate coffee shop, the Lantern, which was named the best in Iowa by the Food Network. I stopped in at the Lantern, a big exposed-brick space with fancy espresso equipment, to meet with Joshua Harms, a spider web developer and local troublemaker who became a Get-go Amendment cause célèbre this year after the boondocks threatened to sue him if he didn't take down his website, shouldyoumovetosibleyia.com, which documented a foul odour emanating from one of Sibley'due south major businesses, a grunter-blood processing plant. The ACLU championed Harms's instance and sued Sibley. The town quickly folded, wrote Harms an apology, and agreed to train its staff and lawyers in First Amendment law. The case made international headlines and embarrassed Sibley.

Harms is a Bernie Sanders supporter, which makes him an outlier in the town. Sibley is the seat of Osceola County, which voted 79 percent to 17 pct for Trump over Clinton, making it i of the well-nigh pro-Trump bastions in America. Steve King won the county in 2016 with a similar margin. The locals "tend to exist very conservative, and of grade they all are Trump backers," said Nelson. Art Cullen, a Pulitzer prize–winning journalist at the nearby Storm Lake Times, told me that much of the population is "Dutch Reformed and very religious." And then I was only a little surprised when the owner of the coffee store, Brenda Hoyer, asked, "Are you a believer?" equally she came over to take my gild. I muttered something about growing up Catholic and ordered an iced tea.

Hoyer'due south extended family, including grandkids, were milling around the store. The identify had a welcoming family vibe and more diverseness than you lot might await. I noticed several Hispanic women eating pastries and speaking Spanish at a nearby table. Sibley is actually eight per centum Hispanic, and that growing population largely provides the labor for the area's meatpacking, poultry, and dairy industries. Immigrants are essential to Iowa, which has an estimated forty thousand undocumented residents, mostly Hispanics, according to a 2014 report from the Pew Research Center. I was visiting the country but days after police force found the body of Mollie Tibbetts, who was allegedly killed past an undocumented worker from a dairy farm, and anybody was talking about immigration. In a speech communication, Trump had used Tibbetts's murder as a cudgel to bash "Democrat immigration policies" that he said were "spilling very innocent blood."

Hoyer and I talked about Trump. She admitted she wasn't crazy about the tweets and his messy personal life. She liked Mike Pence and noted "it would be a good bargain" if Trump were impeached and replaced by Pence. When I told her I was working on a story about dairy farms, her ears perked up. She and her husband, Gene, were dairy farmers and had recently sold their business. "You should talk to Gene," she said. When I mentioned Trump'southward immigration policy, she was quick to add together, "Well, we don't concur with him on that!"

And then she told me something that knocked the wind out of me: "My son recently took his life." It came out of nowhere, and I barely knew how to respond. His name was Bailey. He was seventeen and he had died thirteen days ago. This was the first day the coffee store had been open since his expiry. I noticed a Bible verse in chalk behind the counter: "Do not fearfulness for I have redeemed you. I have summoned you by name. You are mine." The Lantern, I later learned, was actually a ministry that, co-ordinate to its website, provides "a safe place where everyone is welcome." I liked information technology in that location and decided to arrive my office while I was in Sibley.

Jerry Johnson, Sibley's mayor, walked in. He was wearing golf attire, and any ill will existed between him and Harms over what Harms called "the blood found" seemed to have faded. Perhaps because of the town's troubles with Offset Amendment police force, Johnson was especially gracious to me. I explained why I was in Sibley, and he immediately suggested that I stop by Anthony Nunes Jr.'s firm to interview him. When the subject area turned to Trump's nil-

tolerance policy on immigration, the mayor replied with what was already condign a familiar refrain: "I don't hold with him on that!"

The Nunes family dairy, NuStar Farms LLC, sits on xl-three acres surrounded by corn on the southern outskirts of Sibley, off Highway lx, a main route between Sioux City and Minneapolis. According to Dairy Star, they have about 2 thousand Jersey cows. A source told me that NuStar sells virtually all of its milk to Wells, an water ice foam company in Le Mars, which makes the Blue Bunny brand. The NuStar cows are housed in 2 seven-hundred-pes, white aluminum barns that are the most prominent feature of the farm. The western sides of the barns are outfitted with dozens of steel ventilation fans that wait similar rocket engines from a distance, nigh every bit if a pair of space-shuttle boosters had dropped in the middle of a cornfield. I visited during silage season, when dairymen are out cutting corn to make winter feed for their cows. It had only rained, and the odour of fresh silage, similar an intense version of freshly cut grass, filled my auto as it rumbled down a dirt road to NuStar. As I approached the dairy, a white Yukon SUV exited from NuStar's muddy parking lot and passed me. I saw Anthony Nunes Jr. in the cab of a tanker truck. Instead of bothering him at work, I decided to take the mayor's advice and visit him at home the next day.

It didn't get well.

I found the Nunes home on the far north edge of town, where the leafy neighborhood bumps up against the surrounding farmland. In the driveway was another white Yukon—the fancier Denali version. Anthony Jr. was pulling out of the driveway in a farm truck. I waved at him, and he abruptly stopped the truck in the street and walked over to my machine. He was wearing jeans and a work shirt. I told him my name and asked him if I could talk to him for an article about his dairy. "I'1000 taking your license plate downwardly and reporting y'all to the sheriff," he said. "I don't want to exist bothered." I asked him once again if I could interview him and he repeated himself, but this time a lot louder. "I don't want to be bothered anymore." As he walked to his truck, he looked back and warned me: "If I come across yous again, I'm gonna get upset." Patently Sibley's Outset Amendment training hadn't filtered downwards to all its residents.

Other dairy farmers in the area helped me understand why the Nunes family might exist and so secretive about the farm: Midwestern dairies tend to run on undocumented labor. The northwest-Iowa dairy community is small. Most of the farmers know one another, and well-nigh belong to a regional trade grouping called the Western Iowa Dairy Alliance (though WIDA told me NuStar is non a member). One dairy farmer said that the threat of raids from Ice is so acute that WIDA members accept discussed forming a NATO-like pact that would treat a raid on 1 dairy every bit a raid on all of them. The other pact members would provide labor to the raided dairy until it got back on its feet.

In every conversation I had with dairy farmers and industry insiders in northwest Iowa, it was taken as a fact that the local dairies are wholly dependent on undocumented labor. The low unemployment rate (it's 2 percentage in Osceola County), the depression turn a profit margins in the dairy concern, and the global glut of milk that keeps prices depression make hiring exterior of the readily available puddle of immigrants from Mexico and Guatemala unthinkable.

"Eighty percent of the Latino population out here in northwest Iowa is undocumented," estimated i dairy farmer in the area who knows the Nunes family and often sees them while buying hay in nearby Rock Valley. "It would be slap-up if we had enough unemployed Americans in northwest Iowa to milk the cows. Simply at that place'southward just not. We accept a very tight labor pool effectually here." This person said the system was broken, leaving dairy farmers no choice. "I would love it if all my guys could be legal."

The farmer explained that all the dairies require their workers to provide bear witness of their legal status and pay the required country and federal taxes. But it's an open up clandestine that the organization is built on easily obtained fraudulent documents. "I merely wait at the document—Hey, this looks like a good commuter's license, permanent resident carte, whatever the instance is—and that's what you go with," the farmer said. A 2d northwest-Iowa dairy farmer who knows the Nunes family told me, "They show you a Social Security carte, we take out Social Security taxes. Where'd they get the card? I accept no thought." I asked what the chances are that a farm the size of NuStar uses only fully legal dairy workers. "It's adjacent to impossible," the first dairy farmer said. "In that location's no dang way." This was speculation, only here is the logic that informed it: About workers start at fourteen or 15 dollars an hr, the get-go farmer said. If dairies had to use legal labor, they would likely accept to raise that to eighteen or 20 dollars, and many dairies wouldn't survive. "People are going to get broke," the farmer said. The story was similar in the poultry, meatpacking, and other agricultural industries in the expanse.

What this person was describing was difficult to wrap my head around. In the heart of Steve Male monarch's district, a place that is more pro-Trump than about any other patch of America, the economic system is powered by workers that King and Trump have threatened to arrest and carry. I checked Anthony Nunes Jr.'s campaign-donor history. The only federal candidate he has e'er donated to, too his son, is Steve King ($250 in 2012). He also gives to the local Republican party of Osceola County, which, records evidence, transfers money into King'southward congressional campaigns.

The absurdity of this situation—funding and voting for politicians whose core hope is to implement immigration policies that would destroy their livelihoods—has led some of the Republican-supporting dairymen to rethink their political priorities. "Everyone's got this feeling that in agriculture, we, the employers, are going to exist criminalized," the first surface area dairy farmer I had spoken to said. "I've talked to Steve King face-to-face, and that guy doesn't care ane iota near us. He does not care. He believes that if you have i undocumented worker on your place, you should probably go to prison house and we need to get as many undocumented people out of here every bit possible." (A spokesman for Rex did not respond to multiple interview requests.) The second dairy farmer, speaking of Trump's and King'south views on undocumented immigrants, added, "They want to send 'em all back to Mexico and accept them get-go over. What a crock of malarkey. Who's gonna milk the cows?"

Later on my encounter with Anthony Jr., I met Jerry Nelson, the Dairy Star reporter, downwards at the Lantern. He wasn't surprised by the hostility. Think about the story from the family unit's perspective, he told me: "They are immigrants and Devin is a very stiff supporter of Mr. Trump, and Mr. Trump wants to shut down all of the clearing, and here is his family benefiting from immigrant labor," documented or not.

Brenda Hoyer came past and said hello. I told her that I hoped it was okay to apply her java shop for interviews. "Sure," she said, "if you're kind and truthful and honest."

I asked Nelson what would happen, hypothetically, if ICE raided every dairy subcontract in the area tomorrow. "It would be a disaster for the dairies," he said. "They would suddenly have nobody to milk or feed the cows. I don't know what they would do." The bell on the Lantern's front door rang, and Hoyer huddled in the corner with a chubby man with nighttime, curly hair. Later on a few minutes, she came back over.

"Yous have a phone phone call," she told Nelson.

"A phone call?" he asked. It made no sense. Everyone who knew where he was would telephone call his prison cell. She asked him to come with her. A few minutes later, he returned in a panic and gathered his belongings. "Nosotros gotta go!" he told me.

On the way out I talked to Hoyer. Her demeanor had inverse. I asked if I could still talk to Gene, her husband. She said it was no longer possible. I had to get out the java shop, she told me. "This commodity," she said, "is going to destroy families." As I walked out, I noticed the mysterious chubby human being eyeing me.

Nelson was freaked out. There was no phone call, of course. The mysterious chubby man had asked Hoyer to have us ejected. According to Nelson, she had told him that an article almost dairies and immigration would "destroy our lives out here." It was an incredibly sensitive subject. "It'south kind of a tertiary rail among dairy farmers," Nelson said. "Whenever I get to a dairy subcontract, I never inquire about the immigrant-labor affair unless they bring it up themselves."

Later Nelson left me a phonation mail in which he tried to explicate the reaction. "Dairy farmers are very deeply patriotic and American, and all the same here they are hiring these people who are not American," he said. "And maybe they feel a niggling shame over that or feel like they are exploiting [people] and they don't want that to come up to light."

Mayor Johnson was concerned virtually the run-in with Anthony Jr. He had suggested that I knock on the man's door, and now he felt like the awkward encounter was his mistake. He said he'd in one case had his own foreign experience. A few years ago, the mayor reported one of Anthony Jr.'south workers, who was Hispanic, to the sheriff's part because Johnson believed the worker's yard was so messy it constituted a violation of the city property code. Co-ordinate to Johnson, Anthony Jr. called the sheriff on the worker'due south behalf and insisted that the merely reason anyone had complained was that they were prejudiced. (Several people I talked to in Sibley assumed Anthony Jr. himself is Mexican, not Portuguese, and he has no uncertainty experienced bigotry himself.)

The mayor, though, was impressively aware when it came to Sibley'southward immigrant population. Perhaps considering of the Nunes debacle, he invited me to his office to talk to him and the city administrator, Glenn Anderson. "I told him to go see Nunes, and that didn't go very adept," he told Anderson equally we sat downward.

Anderson voted for Trump, only he exploded every Trump myth nearly clearing. The ascent in Sibley's Hispanic population hasn't been accompanied past a rise in crime. Most of the crime in Sibley is connected to drug-related traffic stops on Highway 60, he said. Kevin Wollmuth, a deputy in the county sheriff's office, told me that the rise in immigration "doesn't have any bearing on our crime rate at all." Worried that the community is underrepresented in metropolis government, Anderson has tried to get the Hispanic population to run for city council, though without much success yet. He had no interest in knowing what anyone's clearing status was. "If I run into something, I'grand not going to report it to ICE," he said. "It's not my job." He added, "That's not to say that everybody in town that lives here is legal. We don't go knocking door-to-door to say, 'Are you, are you lot not?' " He had much the aforementioned view of the local immigrant population equally Rob Tibbetts, Mollie'south father, who two days earlier had said at a memorial service for his daughter, "The Hispanic community are Iowans. They have the same values as Iowans. As far as I'thou concerned, they're Iowans with ameliorate nutrient."

Sibley is emblematic of a lot of minor towns in Iowa that are dependent on an agronomical economy: They know they cannot survive without immigrants, and they have worked hard to integrate the foreign-built-in population, despite the legal limbo faced by employers and employees alike. When I asked what would happen if ICE turned its attention to Sibley, the mayor shuddered. Anderson noted that he has never seen an Water ice agent in the 4 years he'due south been at his job. He didn't seem eager to go to know any. "If they come in boondocks, so we have to talk about information technology, find out what's going on, why, whether to participate, and make sure our town'southward not disrupted," he said. I asked him what he thought of King's view that all undocumented immigrants should exist deported. He paused and said, diplomatically, "He has a right to his opinion."

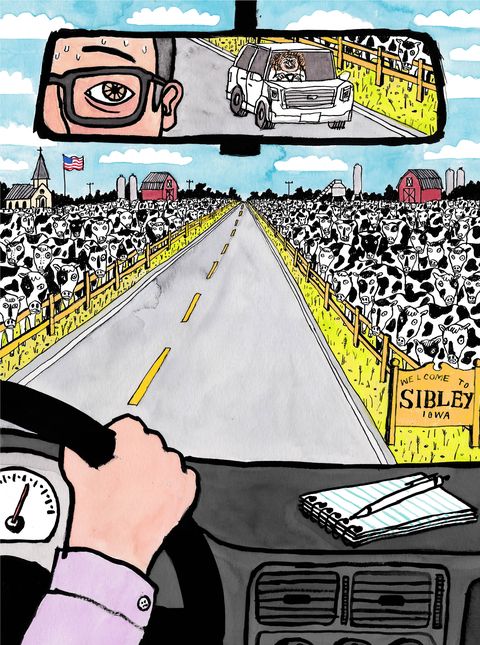

When I walked in the front door of the mayor's office, I had noticed a mud-spattered white Yukon parked outside. Every bit I was driving to my next interview, I looked in the rearview mirror and noticed the white Yukon once more. I drove frantically, crisscrossing streets from one cease of town to the other. Everywhere I turned, the white Yukon appeared. I was existence followed. When I turned the tables and followed the car dorsum, information technology raced off. We played true cat and mouse like that for more than an hour until I finally got a skilful glimpse of the driver: Information technology was a middle-aged woman with curly, red pilus who had a cell phone stuck to her left ear. The cat-and-mouse game started to feel a little dangerous, so I left boondocks for a couple hours. On my way back into Sibley, the aforementioned automobile passed me on the highway. This fourth dimension, the chubby human from the Lantern was driving. He smiled and waved.

Or maybe I'd made a error. White SUVs are common. Could I actually be sure that was the same guy and the same Yukon? A woman was driving the auto earlier; now it was a human being. It didn't make sense. Maybe I was just existence paranoid.

I had a peculiarly sensitive interview that afternoon with a source who I knew would be taking a risk past talking to me well-nigh clearing and labor at NuStar. When I arrived, we talked for a few minutes earlier the source's prison cell phone of a sudden rang. The conversation seemed strained. "Sí, aquí está," the source said. I learned that on the other end of the telephone was a man named Flavio, who worked at NuStar. Somehow Flavio knew exactly where I was and whom I was talking to. He warned my source to end the conversation. Not only was I being followed, just I was also being watched, and my sources were being contacted by NuStar.

I left and drove to the local grocery shop, where I parked in the open up, hoping to draw out whoever was tailing me. I suddenly noticed a human being in jeans, a piece of work shirt, and a baseball cap pulled down low. He was talking on his cell phone and walking suspiciously. Was he watching me? I held upward a camera to take pictures and he darted away. I followed. His machine was parked haphazardly on the side of the road half a cake away. He got in and took off while I followed. Information technology was a dark Chevrolet Colorado pickup truck—with California license plates. I ran the license-plate number through a database. The machine was registered in Tulare, California.

On Dec 13, 2011, Ice agents raided the home, concern, and farms belonging to Mike Millenkamp, a dairy farmer in eastern Iowa. It was the commencement of a vii-yr ordeal that would upend Millenkamp's life. At the time of the raid, he had just iv employees. Three of them were undocumented. Ice hauled away his business records, arrested his employees, and launched an aggressive investigation. After sifting through his files, the government said that about iii quarters of the thirty-eight workers he had employed over a 4-year period were undocumented. Millenkamp pleaded guilty to "illegal alien harboring" and agreed to pay $250,000 in fines and penalties. Despite a relatively clean record, he was sentenced to three months in federal prison and three years of supervised probation, which just ended this past summer.

Prosecutors used Millenkamp to send a alarm to other Iowa dairy farmers. Every bit role of his plea deal, they forced him to submit an op-ed to major Iowa newspapers describing his experience. His commodity, which was preapproved by the local U. South. chaser'southward function, appeared in The Des Moines Annals on June 29, 2016. "If y'all utilize someone you know is not legal, you are committing a federal crime," he wrote.

The Millenkamp prosecution seemed unjust—capricious. And information technology helped explain the reaction I received in Sibley. "That'due south why they are and so concerned," Nelson told me when I mentioned that I was being followed and that my sources were being harassed. "They think you are going to mess with their lifestyle or accept information technology away, interfere with it."

He and I discussed the ethics of reporting on clearing and politics. What if an commodity triggered an Ice raid? Was there even a story here, anyway? Devin Nunes was the public figure at the heart of this, and he had no financial interest in his parents' Iowa dairy operation. On the other hand, he and his parents seemed to have curtained bones facts virtually the family unit'due south movement to Iowa. Information technology was suspicious. And his mom, who co-owns the Sibley dairy, is also the treasurer of his campaign. In 2007, Devin and his wife, Elizabeth, used the NuStar dairy's Iowa post-office-box address on a filing with the SEC regarding a financial holding company the family co-owns, even though Devin and Elizabeth live in California.

And fifty-fifty without the connexion to Devin, who is i of Trump's near important allies, at that place was a bigger story. The American dairy industry is at the heart of an international merchandise war. Trump frequently attacks Canada for protecting its dairy farmers. "We love Canada," Trump said on September 18. "They cannot continue to charge usa 300 percent for dairy products." At a hearing on the consequence in March, Nunes attacked Canada for "getting away with murder in their dairy industry." Canadian officials have responded by noting that the American dairy industry is artificially protected past both federal subsidies—NuStar, co-ordinate to figures based on USDA numbers, has received $140,938 since it started—and its reliance on low-wage, undocumented labor. "The manufacture itself in the Usa has admitted they wouldn't be viable if they couldn't utilize undocumented workers," a former Canadian trade minister, Ed Fast, recently complained to the state'due south Financial Post. The same could be said for much of the broader American agricultural industry—from poultry to meatpacking to grape-picking to cotton fiber—which represents 6 pct of the U. South. economy.

In that location is massive political hypocrisy at the centre of this: Trump's and Male monarch's rural-farm supporters embrace anti-immigrant politicians while employing undocumented immigrants. The greatest threat to Iowa dairy farmers, of class, is not the press. It's Donald Trump.

Just that's not how the Nunes family patently saw it. On my 3rd day in Sibley, I became used to the cars tailing me. In the morning, I was followed past the redhead in the muddy white Yukon. In the afternoon, there was a shift change and I was followed past a unlike, later-model white Yukon. I stuck a GoPro on my dashboard and left it running whenever I parked my car. When I reviewed the videos, one of the ii Yukons could e'er be seen slowly circumvoluted as I ate lunch or interviewed someone.

There was no doubt about why I was being followed. According to two sources with firsthand knowledge, NuStar did indeed rely, at least in office, on undocumented labor. One source, who was deeply connected in the local Hispanic customs, had personally sent undocumented workers to Anthony Nunes Jr.'due south farm for jobs. "I've been in that location and bring illegal people," the source said, asserting that the farm was aware of their status. "People come here and ask for work, and so I send them over there." When I asked how many people working at dairies in the expanse are documented citizens, the source laughed. "To be honest? None. One per centum, maybe."

The source added, "Who is going to go work in the dairy? Who? Tell me who? If people take papers, they are going to go to a expert company where you can get benefits, you lot tin can become Social Security, yous can get all the stuff. Who is going to go [work in the dairy] to brand fourteen dollars an hour doing that thing without vacation time, without 401(k), without everything?"

A second source, who claimed to exist an undocumented immigrant, as well claimed to have worked at NuStar for several years, only recently leaving the dairy, which this source estimated employed about fifteen people. (Equally a rule of thumb, dairies need one employee for every 80 to one hundred cows, so fifteen workers would be a lean operation given the dairy'due south ii-m-head herd.) The sometime NuStar employee, who is eye-anile, claimed to take arrived in the United States from Republic of guatemala in 2011. This source was nervous to talk to me and did not want to speculate nearly the clearing condition of young man employees. "I worked for Anthony for iv years," the source said, speaking in Castilian through a translator. "First milking cows and after that feeding the baby calves." It was "very hard work," but the employee and others were "treated well."

A tertiary source, who claimed to piece of work at a nearby dairy, non NuStar, explained what the local dairy jobs are like. This source claimed to be eighteen years old and to have come from Republic of guatemala ii years agone, afterward paying smugglers $x,000, raised past extended family, to provide transit through Mexico and across the U. S. border. The source said the pay at the dairy was fourteen dollars an hour for milking cows twelve hours a mean solar day, six days a week, which, after taxes—the source had provided the dairy with a simulated Social Security number—worked out to about $1,600 every ii weeks. When I asked how many dairy workers in the area are undocumented, the source replied, "Todos"—everybody.

When I left the interview with the third source, I got in my car and reviewed the GoPro footage. The automobile had been circled by the newer white Yukon the unabridged fourth dimension I was gone. I decided I needed to go out of Sibley for a while and get some communication most how to tell this story ethically. So I collection to Worthington, Minnesota, to meet a priest.

Worthington is simply over the border, less than thirty minutes away. I found Father Jim Callahan at his kitchen table, wearing a Hawaiian shirt and chain-smoking Winstons. Worthington, which is five times the size of Sibley, is a hub for Hispanic immigrants in the Midwest. The influence is unmistakable as you bulldoze down the main street, which is dominated by stores and restaurants that cater to the Hispanic population. More than 70 percent of the students in the local unproblematic school speak Spanish as their outset language. Callahan, whose church building, St. Mary's, conducts Mass in both English language and Spanish, estimates that ninety percent of the Hispanic population in the metropolis is undocumented.

Trump'south election was a seismic effect here. "Absolute fear" is how Callahan described the postelection atmosphere. "Some people were maxim they're going back. Then we saw spikes in domestic abuse, alcoholism, drug addiction." In December 2016, he declared St. Mary'due south a sanctuary church building, which ways it shelters undocumented immigrants and protects them from abort and deportation. "Water ice has been active," he said. "They're in town two or three times a week." He added, "But they haven't targeted farms as such yet."

I laid out the facts I had uncovered in Sibley, including the intimidation of sources and the Devin Nunes angle, and asked him for communication. "I'd tell that story," he said. He paused and added, "We're a sanctuary church, if you demand a place to stay. You're prophylactic here!"

On the way back to Sibley, I stopped at Hawkeye Bespeak, the highest elevation (1,670 feet) in Iowa, and flipped through my GoPro videos and pictures, zooming in on the drivers and cars. I clicked over to Facebook and searched for any Nuneses in Sibley, Iowa. I saw some familiar faces. It all started to click. At that place was the redheaded woman from the muddied white Yukon; she was Devin's sis-in-police force, Lori Nunes. At that place was the chubby guy with curly pilus from the Lantern who had likewise waved at me from the aforementioned Yukon; he was Devin's brother and Lori'due south husband, Anthony Nunes III. There was the woman from the newer Yukon. I zoomed in on a motion-picture show of the auto's license plate: nustar. Not very subtle. The commuter was Devin's mother and entrada treasurer, Toni Dian Nunes. The guy in the pickup truck with California plates was, of course, Devin's dad, Anthony Jr.

I learned that Anthony Jr. was seemingly starting to panic. The adjacent 24-hour interval, the 2009 Dairy Star article well-nigh NuStar, the ane that made me think the Nuneses were hiding something and that had led me to Sibley in the start identify, was removed from the Dairy Star's website. Anthony Jr., I was told, had called the paper and demanded that the editors take the ix-twelvemonth-old story downwards. They relented. The article wasn't captured by the Net Archive, which provides cached versions of billions of web pages, and it tin can no longer be found anywhere online. According to someone who talked to him that twenty-four hours, Anthony Jr. allegedly said that he was hiring a lawyer and that he was convinced that his dairy would soon exist raided by ICE. (Is it possible the Nuneses have nada to be seriously concerned about? Of course, but I never got the chance to inquire considering Anthony Jr. and Representative Nunes did non respond to numerous requests for interviews.)

I hope Ice stays the hell abroad from Sibley. The immigration system that powers Iowa's dairies is undoubtedly cleaved. The dairy owners live with the ever-present fear of condign the side by side Mike Millenkamp. The undocumented workers live in the shadows and, especially in the era of Trump and zero tolerance, constantly fear arrest and displacement. Meanwhile, Republicans in Congress, including Devin Nunes (per his CaRepublican website), have decided that unwavering support for ICE is crucial to their efforts to attack Democrats and help the GOP keep control of the House of Representatives after the midterm elections. Naturally, the prospect of passing legislation that would create a invitee-worker program for dairy workers who are undocumented—an idea overwhelmingly supported by the industry—is a fantasy in the current environment; Trump, King, and their allies describe such policies as "amnesty." The Washington debate is completely discrete from what is actually going on in places like Sibley.

The relationship between the Iowa dairy farmers and their undocumented employees is indeed fraught. I cringed at the fashion some of the dairy farmers talked about their "help." When I asked one dairy farmer, who admitted many of the farm'south workers are undocumented but who also inexplicably claimed to be "very supportive of Trump" and "kind of in favor of his immigration laws," what a solution would be, this farmer suggested a guest-worker program just compared the workers to farm animals. "It's kind of similar when you bought cattle out of South Dakota, or anyplace, you lot ever had to have the brand inspected and you had to have the brand canvas when you hauled them across the state line," the farmer said. "Well, what's the difference? Why don't they have to written report to the metropolis hall or county role and say we're hither working and everybody knows where they're at?"

As bad equally this paternalistic and exploitative system tin can be, Nelson and the dairy farmers insisted that most dairies are family-endemic and -operated and that the workers, documented or non, oftentimes become part of the family. This somewhat clichéd view tin be overblown and sometimes used to defend an unfair organisation, only the sentiment helped me understand Brenda Hoyer's spooky alarm to me at the Lantern. During her son's wake, 4 Hispanic employees from their old dairy came to express their condolences. They had worked at that place so long that their children refer to her husband, Factor, as Grandpa.

According to someone he told the story to, Gene received them and thanked them. "I've lost a son," he said to the four men, "simply I yet have four others."

This article appears in the November '18 issue of Esquire. Subscribe

This content is created and maintained past a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more than information about this and similar content at piano.io

sandovalsuccionoth.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.esquire.com/news-politics/a23471864/devin-nunes-family-farm-iowa-california/

0 Response to "Devin Nunes Made an Ass of Himself Again"

Post a Comment